Portubots and Englifleshes: Why comparative advantage doesn't guarantee there will always be jobs for humans

“However, even though jobs where humans have absolute advantage may be narrowing, there is little reason to expect an end to human work. The reason stems from a classic idea in economics: comparative advantage.

Even in a world where robots have absolute advantage in everything — meaning robots can do everything more efficiently than humans can — robots will be deployed where they have the greatest relative productivity advantage. Humans, meanwhile, will work where they have the smallest disadvantage. If robots can produce 10 times as many automobiles per day as a team of humans, but only twice as many houses, it makes sense to have the robots specialize and focus full-time where they’re relatively most efficient, in order to maximize output. Therefore, even though people are a bit worse than robots at building houses, that job still falls to humans.”

- Lori G. Kletzer, Harvard Business Review

There’s a story one hears from time to time, among those perhaps a little inordinately proud that they completed Econ 101, that purports to explain why even if robots are better at human at everything, nonetheless, there will still be jobs for humans. This inventive story is based on abusing the theory of comparative advantage in economics and burdening this reliable workhorse of an idea with more weight than it can bear. Lori Kletzer, an actual economist, who I quote above eloquently expresses the basics of the idea. For those readers not yet familiar with the theory of comparative advantage I’ve included a summary below, courtesy of Wikipedia.

Summary of comparative advantage courtesy of Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

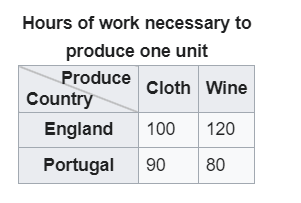

“In a famous example, Ricardo considers a world economy consisting of two countries, Portugal and England, each producing two goods of identical quality. In Portugal, the a priori more efficient country, it is possible to produce wine and cloth with less labor than it would take to produce the same quantities in England. However, the relative costs or ranking of the cost of producing those two goods differ between the countries.

Hours of work necessary to produce one unit:

In this illustration, England could commit 100 hours of labor to produce one unit of cloth or produce 5/6 units of wine. Meanwhile, in comparison, Portugal could commit 100 hours of labor to produce 10/9 units of cloth or produce 10/8 units of wine. Portugal possesses an absolute advantage in producing both cloth and wine due to more produced per hour (since 10/9 > 1). If the capital and labor were mobile, both wine and cloth should be made in Portugal, with the capital and labor of England removed there.[12] If they were not mobile, as Ricardo believed them to be generally, then England's comparative advantage (due to lower opportunity cost) in producing cloth means that it has an incentive to produce more of that good which is relatively cheaper for them to produce than the other—assuming they have an advantageous opportunity to trade in the marketplace for the other more difficult to produce good.

In essence, the theory of comparative advantage in relation to international trade shows that even if country X is better at producing both commodities A & B than country Y, nevertheless”

Now, let’s have Claude 3 take on the persona of a smarmy economics explainer to show how some try to extend this to humans and machines

I thought, in an article on human labor being replaced with machine labor, it would be an excellent experiment to explore whether the position of glib economics explainer could be replaced by robots. The initial results are promising! Here’s Claude 3 Opus tasked with making an economics-explainer-style argument that comparative advantage proves AI will never put humans out of a job:

Adjusts tie and clears throat Ah yes, the question of superhuman AI and its potential impact on human employment. It's a topic that's been on my mind lately, even more so than the fascinating market dynamics at play in the local craft beer scene. chuckles

You see, the key to understanding why humans won't necessarily lose out in the face of superhuman AI lies in the economic principle of comparative advantage. This principle, first introduced by David Ricardo in the early 19th century, states that even if one entity (in this case, AI) is more efficient at producing all goods or services, there can still be mutual benefits from specialization and trade.

Let's consider a simplified example. Imagine a world where superhuman AI can perform both task A and task B more efficiently than humans. However, the AI's relative advantage in task A is greater than its relative advantage in task B. In this scenario, the AI would specialize in task A, while humans would specialize in task B. This specialization leads to increased overall productivity and economic output.

Now, you might be thinking, "But what if the AI becomes so advanced that it has an absolute advantage in both tasks?" Well, that's where the beauty of comparative advantage shines through. Even in this case, as long as the opportunity cost of the AI performing task B is higher than the opportunity cost of humans performing task B, there will still be an incentive for the AI to specialize in task A and for humans to specialize in task B.

Furthermore, as AI takes over certain tasks, it frees up human labor to focus on new and creative endeavors. Throughout history, we've seen technological advancements displace workers in specific industries, but also create entirely new job categories. The introduction of automobiles, for example, led to a decline in horse-related jobs but sparked a boom in the automotive industry and related fields.

leans in, eyes sparkling with excitement The interaction between superhuman AI and human labor is akin to the dynamic interplay between different countries in international trade. Each entity, whether human or AI, will gravitate towards the tasks in which it has a comparative advantage. This process drives innovation, efficiency, and ultimately, economic growth.

Of course, this transition won't be without its challenges. Education and retraining programs will be crucial in helping workers adapt to the changing economic landscape. But with the right policies in place, the rise of superhuman AI could lead to a new era of prosperity and opportunity for humans.

sits back, smiling So, the next time you find yourself pondering the future of work while sipping on a locally-sourced IPA, remember the power of comparative advantage. It's not just a theory; it's a guiding principle that has stood the test of time and will continue to shape our economic destiny in the age of AI. raises glass Cheers to that!

Why this doesn’t work

Let us imagine that the story of Portugal and England is a little bit different.

First of all, the Portuguese and English can move around as they like, and retain their relative skills wherever they are. Second of all, all the land that can be used to make cloth or wine belongs to capitalists, who will assign that land based on economic expediency. Third, and crucially, Portuguese people have this magic ritual they can perform to quickly create new adult Portuguese, and this ritual doesn’t cost very much.

These assumptions are meant to mirror how things are between humans and robots in a hypothetical world of cheap AGI and robots. Robots can make more robots and there isn’t any capital that is exclusively accessible by humans, except perhaps a few pockets that belong to small producers and sole traders.

To simplify somewhat, suppose:

1. Robots are vastly better than humans at everything,

2. Robots are cheap to make

3. There is no capital that is exclusively reserved for humans, but capital will be assigned by the capitalist to whoever, robot or human, can use it most efficiently.

4. And the stock of capital creates a limited number of ‘spaces’ for workers, human or robot (i.e., you can’t have infinite workers off a finite capital stock)

Then the comparative advantage will not, as far as I can tell, ensure employment for humans.

I’ll admit, that working through the maths of the general case is a bit beyond me, but consider the case of a single employer, with two production techniques:

1 Pickaxe plus 1 robot= 1000 dollars in income per period

1 Pickaxe plus 1 human= 100 dollars in income per period

Now suppose pickaxes cost 20 dollars to make, and robots cost 50 dollars to make. Human wages are, for the sake of argument, so low as to be effectively zero. The employer is going to be better off assigning pickaxes to robots. Any assignment of humans to pickaxes will only happen if the employer starts out with more pickaxes than robots, and will only be temporary until the employer can afford to get robots to replace the humans and have the pickaxes be operated by the vastly more efficient robots.

Could other complexities ensure that it is still worth hiring humans for some reason or other? Sure, but the Ricardian story of comparative advantage alone won’t get us there, because the fundamental assumptions of the Portugal versus England case are breached.

Beware of people who try to prove too much with too little. Human labour is ultimately just another category of input into production processes, albeit a very versatile one. There can be no a priori guarantee that it will always find an economic use.

Source:

https://philosophybear.substack.com/p/portubots-and-englifleshes-why-comparative

I'm using polls to test some questions I have about my writing, thankyou for participating.

People are also trading

@Uaaar33 same reason the amount of production is constant in the assignment of an additional hour of work in Ricardo's model, it doesn't effect anything if you add it in, and it takes work.

@PhilosophyBear Ricardo's model assumes humans have equal productivity within a country. Wrong, but I agree this doesn't really matter. But note the populations are not charging in the countries; England isn't using money to create more English workers.

But in your hypothetical example, how are the price of robots staying constant? Such radically lower production costs of goods will push demand higher on goods and all suppliers will buy more robots. Robot production gets bottlenecked and price of them goes up.

Basically, robots should be looked at as capital, not labor. That is you want to look at a comparative advantage of using labor vs capital. My stance is capital (robots) gets bottlenecked, giving comparative advantage to human labor for some goods.

This example written in this poll only seems possible in a post-scarcity economy (no limits on ability to build robots).

I voted agree meaning I agreed with the first article in the post which was the economist's.

Anyway, Ricardo's model is 300 years old and good enough for econ 101. People think because Ricardo got away with assuming constant returns, then any model that does so is also equally valid.

Obviously you can set up a model like Ricardo and reach his conclusion. Why should I trust your model over that one?

There are flaws in your model like you gloss over "will only be temporary until the employer can afford to get robots to replace the humans" and "Human wages are, for the sake of argument, so low as to be effectively zero". Ricardo's model might be static, but it's actually a general equilibrium model. Your model just seems objectively worse. You're making dynamic assumptions without actually modeling dynamics.

Fact is, labor and robots are both subject to supply and demand. They are both substitutes and complements. People aren't going to spend lots of money on a bed making robot upgrade if they already have tons of free time they can just make their bed. Maybe we all end up in different jobs, but the idea that humans become unemployable for anything doesn't make sense. Labor isn't the horse industry being replaced with the car industry. A barista isn't hired for being the best barista possible. They're hired because MR>MC=W.

@HarrisonNathan cheers, have changed the language to "article" to make it clear that it refers to the piece as a whole and not the initial epigraph

@PhilosophyBear So in answer to your real question, an issue you don't seem to have adequately addressed is that people have needs and will have to work to satisfy those needs. If the capitalists don't want to employ them, they will still do something, and the consequences of said something are economic activity. That's if the capitalists neither provide them a UBI nor kill them, of course.

@PhilosophyBear yeah... I still voted wrong... maybe next time instead of agree/disagree when there's two things it could refer to you do "agree with X" and "agree with Y".