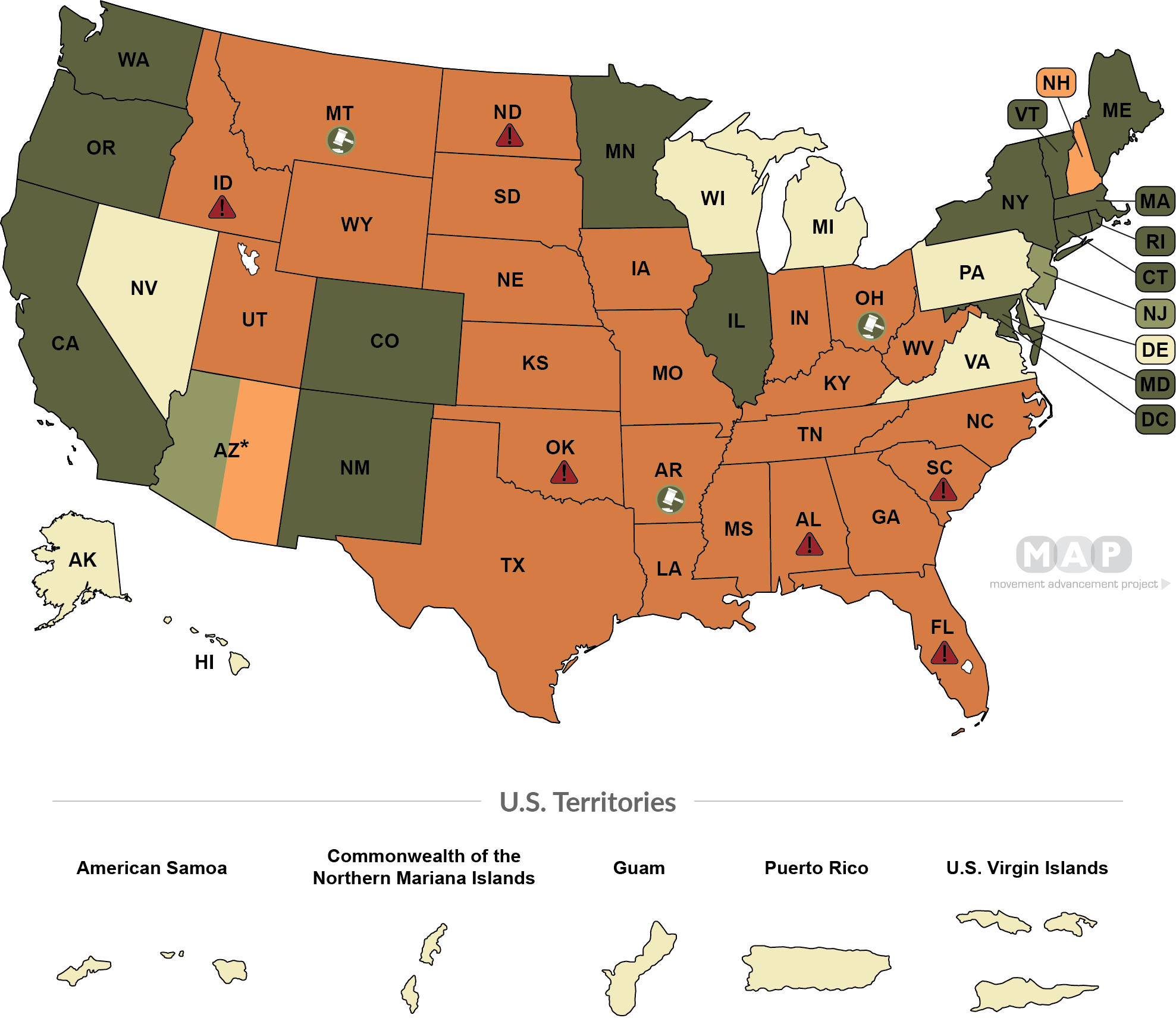

Currently 28% of transgender youth live in states where best-practice medical care for transgender youth is banned, as reported by LGBT MAP: https://www.lgbtmap.org/equality-maps/healthcare_youth_medical_care_bans

If the above source stops reporting data at resolution time, data from Human Rights Campaign (https://www.hrc.org/resources/attacks-on-gender-affirming-care-by-state-map) will be used, or other similarly credible source.

Update 2025-02-11 (PST) (AI summary of creator comment): States Defying Orders and In-Practice Access

If a state law or order banning best-practice care is not effectively enforced (i.e. patients continue to have in-practice access to care), this will count as not being a ban for resolution purposes.

For example, if a state directs healthcare providers to continue offering treatments despite a federal order, then that state would not be considered as banning care, potentially leading to a NO resolution.

Update 2025-02-11 (PST) (AI summary of creator comment): Update from creator

The resolution will use the care standard as it existed at the time the market was created.

Even if a reputable medical body later changes its guidelines or deems the care no longer best-practice for minors, that change will not affect the resolution criteria.

People are also trading

@RiverBellamy Hi River, it's unclear to me what bias you're picking up to here. The question of interest is whether the standard of care available to minors in the U.S. at the time the question was created would continue be widely available in the future.

I hold no position in the market, and have specified which rubrics and independent sources I will defer to if the basis of resolution is unclear.

@lumi I think you do know what I am referring to, because you carefully avoided it. You called puberty blockers and hormones "best-practice". Whether it is, in fact, the best practice, is precisely the point on which people starkly disagree. Nobody wants to hurt these kids. People just don't agree on which action is most likely to hurt these kids. Your wording of the question presumes that one answer is right and the other is wrong. Many people would say that the best practice medical care is probably some kind of counseling without puberty blockers, hormones, or surgery. Almost certainly no state will ban that.

@RiverBellamy The title was chosen because the model of care in question was considered best-practice by medical consensus at the time the question was written. The goal of the question is to get a read on whether this model of care will be widely available in the U.S. going forward.

I don't claim to have no personal views, but I asked this question because I am truly interested in the answer. I intend to resolve it truthfully as per the resolution criteria in the description and not privilege one group of traders over another based on my personal views.

I see your point that noting the specific axes of care would be more informative for traders, and I've made some changes to that effect, as much as I can within the title length constraints.

@TobiasPace If states defy the orders, such that patients can in-practice still access the same care, it may resolve NO. For example, NYS is ordering NYU Langone to continue offering treatments contrary to the federal order.

@lumi Also, for the purpose of this question, in general, I am deferring to LGBT MAP's barometer unless they stop publishing.