See my tweet:

Resolves YES only if Michael Nielsen posts that he agrees in the comments here or on Twitter.

People are also trading

The new paper by Mr Arora and his colleagues, as well as one from 2019 with a slightly different group of authors, makes a subtle but devastating suggestion: that when it came to delivering productivity gains, the old, big-business model of science worked better than the new, university-led one. The authors draw on an immense range of data, covering everything from counts of phds to analysis of citations. In order to identify a causal link between public science and corporate r&d, they employ a complex methodology that involves analysing changes to federal budgets. Broadly, they find that scientific breakthroughs from public institutions “elicit little or no response from established corporations” over a number of years. A boffin in a university lab might publish brilliant paper after brilliant paper, pushing the frontier of a discipline. Often, however, this has no impact on corporations’ own publications, their patents or the number of scientists that they employ, with life sciences being the exception. And this, in turn, points to a small impact on economy-wide productivity.

@PeterF It's 2030 and Michael Nielsen has not posted here or on Twitter that private-only funding for science improves the status quo.

Ruxandra Teslo (a great up-and-coming substacker) writes about this: https://www.writingruxandrabio.com/p/can-the-markets-replace-academic

Alex Tabarrok, GMU economist, questions whether science is a public good: https://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2024/02/is-science-a-public-good.html

H/t @ian for the link!

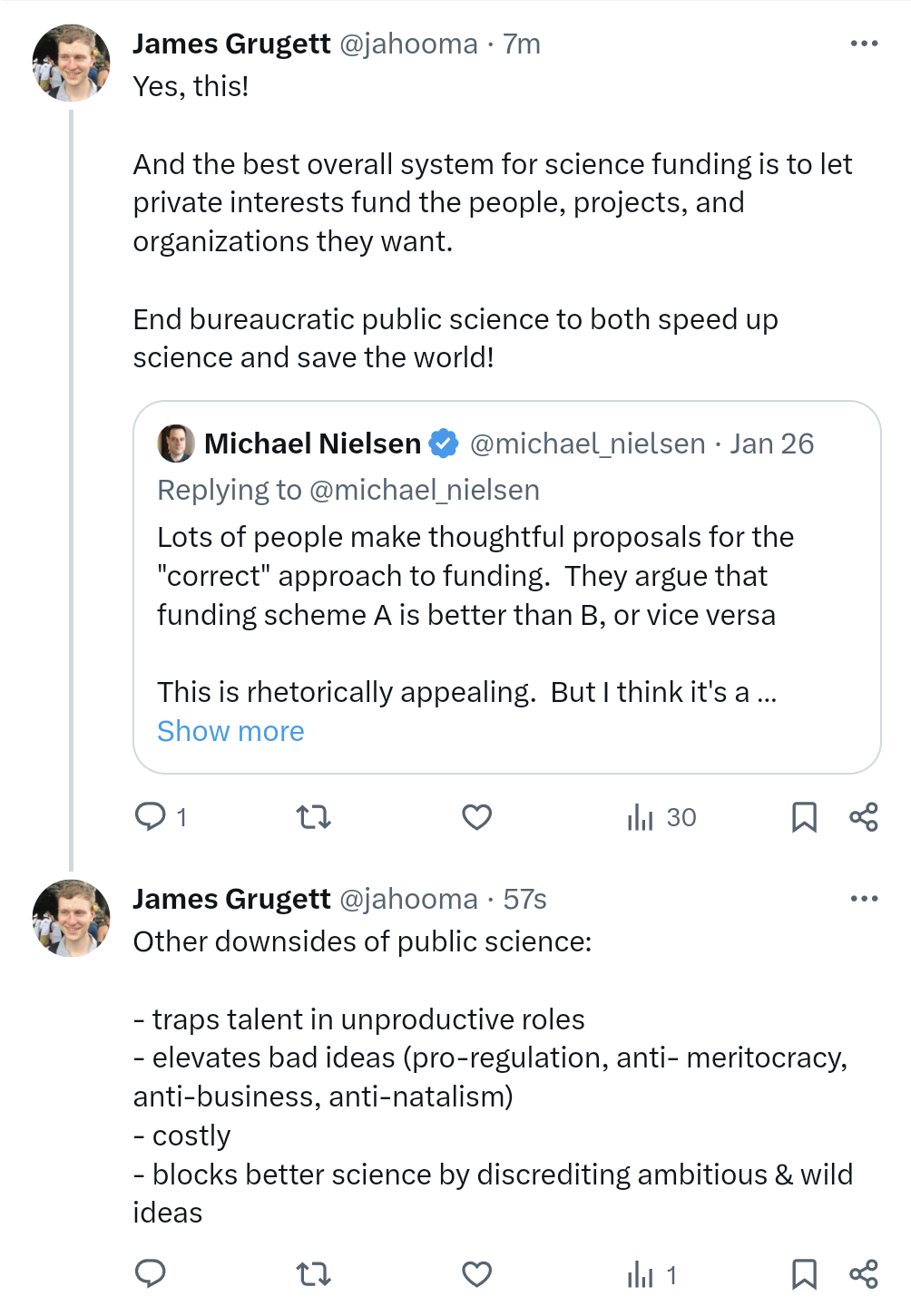

James is trolling as engagement bait.

People argue funding scheme A is better than B

Yes. And the best funding scheme is [...]

@Mira Haha, you could read it that way. But, nope, I'm being sincere!

Private funding for science is a meta-funding scheme. It doesn't say how to fund it. People can come up with any kind of structure they choose.

@JamesGrugett I think you are undervaluing "having a pool of people with the safety to dedicate their lives to learning a niche skill". Somebody spends 30 years studying Ring Theory because there's a tenured position that makes it safe if you really like ring theory. Only the NSA or very few cryptography companies would pay for it, even though it's useful.

If the US doesn't have people that know something, companies aren't going to fund it: They're going to move or outsource to France, Russia, or Poland. And if there aren't tenured positions to study neural networks for 40 years while they're unpopular, people just won't study it and then the countries that do have public education are going to be the AI hotspots because Google/Facebook/etc. are going to hire from there rather than try to teach people locally.

I thought about getting a graduate degree in Mathematics. The job market in academia looked very annoying, so I did less ambitious things like programming software to generate reports for television ads and investing in real estate, until I had a couple million dollars and no longer cared about the job market. The VP of Research at the ad job had a Physics Ph.D and instead of studying Physics he was doing ads; very common for physicists to go into finance and pricing derivatives if they can't land a job at the LHC or a tenure-track position. If there's no good jobs(subsidized by the government), people just don't do science and the labor pool lacks that skill.

So if you keep everything the same and you just cut the funding, people won't study science and there won't be a strong pool for private companies to draw from, and it'll be easier for them to outsource.

USA was a leader in chip fabrication with Intel until Taiwan in 1973 launched the Industrial Technology Research Institute(ITRI). 14 years later(1987), TSMC's founder moves from the US to Taiwan. 36 years later, even with $40 billion is Arizona, people can't make cutting edge competitive fab plants in the USA because there just aren't people here. TSMC's making new backup plants in Japan instead. They're investing here anyways because the US is otherwise a powerful country, but if say Canada wanted a fab industry the government would have to train people and get 0 results for 15 years until there's a base. Private companies aren't going to go to Canada and make them competitive on behalf of Canadians; they'll just take people from Taiwan instead.

Same thing with many other industries. Private companies don't create scientists, engineers, mathematicians, and such; they take people from an already existing pool. That can still be valuable, and you can argue about the exact ratio, but cutting funding entirely just kills the pool.

Typically the best people don't even respond that well to economic incentives, and you can't hire and develop it if there's a sudden need. The guy who specialized for 20 years studying "Functional Analysis with application to Hilbert Spaces in Quantum Mechanics" can't be bought locally at any price if 20 years ago you didn't create the job and he did something else or moved to France. Somebody doesn't study that unless they're genuinely interested and want to advance knowledge. If you try to force it by offering money, the people you get will be worse and mercenary.

But, if there's a pool of public jobs, then yes, Google can come in and hire an entire AI lab away from Carnegie Mellon. And they'll publish lots of cool papers in Reinforcement Learning and renew interest in neural networks, and people will wonder "They're getting so much done. Can't we do that for all science?" But no - you can't. Actually, the Google researchers even publish papers because they have significant leverage over their employer: Most companies would prefer to keep research private by default, but that would kill your academic career and they'd have to buy you for life. Without competition from academic jobs, researchers would have no leverage, there'd be fewer papers published, science would slow down, and the jobs that do exist would either pay less or researchers would do something else like software engineering.

It's one thing to say that the benefits of publicly funded science have been overestimated, and that we should reduce funding. I would still strongly disagree with that take, but at least I can see how a reasonable person might come to believe it. But the idea that ending publicly funded science will have a net benefit at all, let alone that it would somehow speed up science and "save the world" (from what?) makes no sense at all. It wouldn't even be possible to post that take on Twitter if public science didn't exist - we certainly wouldn't be living in the information age without public research and might not have computers at all.

how does the covid vaccine get invented in this model? the NIH funded “dead end” research for decades into mRNA-based vaccines, which wouldn’t float in a strictly for profit model. and if it did survive at some private company (taking pharma at their word that their insane drug prices compensate for years of R&D costs), do we all need to pay insane prices for the jab in the end? what would that have done for vaccine uptake - which was already low and falling?

This doesn’t seem like a good model for health based science, which is a public interest and I would appreciate it if it were paid for with public funds.

@mattyb @JamesGrugett what happens to colleges? so much research at higher education is paid for by public grants. at public universities (some of the top science programs in the WORLD - Cal, UCLA…etc) this is nearly entirely funded by public money (afaik). These schools train the next generation of private industry leaders. They learn their skills in research labs, and many of them continue that work after school.

how does this model evolve when the public money for science ends? are we not cutting off the whole pipeline of future scientists from learning and exploring and practicing? does the private industry suddenly have to fund this all? with what money?

@mattyb My bet is that they're gonna claim that companies will support students through their neverending benevolence. "Look at how much Bezos gives to charity every year! We don't need taxes!"

@Pykess I worked in a lab funded with public money in school. I learned so much there which I would’ve used had I pursued lab-based science. Like half the people I went to school with did continue on and do even more research (some with public funds) and are now just starting to come out and go into the private sector.

I don’t know how that’s possible with strictly private funds. Bezos isn’t doubling his money, so are we just going to have half the scientists able to properly train each year?

I’m all for making sure our taxes are spent more accountably (love to start cutting DoD til they can pass an audit) but the sciences certainly isn’t where I’d cut from. How much of our taxes actually go to fund the sciences anyways? I’d say not enough, short of someone giving me a number.

Also, incredible essay in the other thread!

Science and tech progress was rapid before government funding for professionalized science became a thing after WWII, which suggests at least that public funding is not necessary.

My own impression is that new science funding typically starts well, with motivated and smart people making advances, but that efficiency decays over time from bad process.

The only sustainable solution we've yet discovered is the private ecosystem.

Another place we may disagree is the impact of the bad ideas that public science lends prestige to. I think trillions of dollars are lost because of increased regulation alone, much of which would not happen without misguided academics that were publicly funded.

@JamesGrugett I think private funding is a fine part of scientific funding.

But as we've seen time and time again, privately funded science is often inherently biased: tobacco companies, nicotine companies, Boeing 747 Max 8 and now the Max 9, etc etc.

Worse than that, basic research is inherently unprofitable. So things like fundamental physics, semiconductors, the precursors to vaccines, pure mathematics, element hunting, and many many more would receive little to no funding. In the study of the philosophy of science, it is paramount that science be free from the pressure of profits and results.

Finally, the neverending "regulation bad" argument is so astonishing to me just after the recent reminders from OceanGate and the Boeing Max 8. These disasters were caused directly and wholly due to lack of oversight and regulation. Without oversight and regulation, you have companies knowingly and willingly releasing dangerous deadly products for profit. The UK mad cow disease scandal under Thatcher's leadership, electronic cigarette companies openingly marketing towards children and teenagers, BP knowing about climate change 40 years ago, and the list goes on and on.

If you want to claim that public funding's bureaucracy is a drag, fine. But you've tagged this market "Philosophy of Science". Your position has little to nothing to do with the philosophy of science and rather the philosophy of business.

There is nothing stopping private entities from funding science at the moment, and many, many do. See Google and IBM's battle for non-NISQ quantum computing. But this is because they believe there is profit to be had. Likewise, insecticide and fertilizer research at universities across the US are heavily funded and or sponsored by agriculture companies themselves. Because there is profit in it for them.

But wind turbines? Solar panels? Laser surgery? CRISPR? Spaceflight? GPS? These are all things that started as purely fundamental science and or publicly funded research and no company would have ever taken on the financial risk of funding them, let alone even been able to.

Let me line by line address the points in your tweet:

"traps talent in unproductive roles" Are you claiming that researchers don't have career mobility? If that's the case then all I can say to that is simply "it doesn't." It is exceedingly common for professors, staff scientists, etc to spend parts of their career in academia and part in private industry here in the US. And those that choose to remain purely in academia have ample opportunity to change both their location but more importantly their research topic/direction. Researchers at public institutions freely pursue whatever research interest they have so long as they can find funding for it - be it public/grant OR private. Universities/the government doesn't dictate what researchers at public institutions must work on. These researchers have complete self determination, and (not always, unfortunately) most of the time so too do their students.

"elevates bad ideas (pro-regulation, anti-meritocracy, anti-business, anti-natalism)" I've already address the regulation conspiracy. But also I challenge you to find a single researcher at a public institution or laboratory that will say they want more bureaucratic red tape and government oversight breathing down their necks. Researchers both public and private alike want to be left to do as they please. See the SSC fiasco in the Reagan/Clinton eras for an example of just how much scientists abhorred and avoided oversight. In regards to anti-meritocracy, this is the exact opposite of public academia at the moment. There is a current oft-repeated phase; "publish or perish". The competition for public AND private grants and funding is so tough and has been for so many years, that people feel that they must constantly release ever more impressive results in order to not "perish." Whether or not this is a good thing is besides the point. "anti-business" - what? Every public institution that I know of in the US has IP sharing with scientists. Any discoveries/technologies/etc that researchers find are their intellectual property which they may start business ventures with, so long as the government (who funded the research) has access to it. Many, many pure research scientists have gone this route. For just two examples see IonQ and AeroQ. Two startup quantum computing companies each founded by researchers at public institutions. And I don't have a clue what you're on about with "anti-natalism". I can name exactly two people I've met in academia, who weren't students, who didn't have a family with children. Are you claiming that corporations - which in the US are famous for giving us just so many workers rights and definitely give us the legal right to any time off when having a child - are better in this regard? Please.

"costly": statistics please. I seriously doubt that the $ per person-hour is significantly different between private and public.

"blocks better science by discrediting ambitious and wild ideas": This again is a philosophy of science point. Science is fundamentally a discussion based, peer reviewed, argumentative, iterative process. We have evolved social patterns that maximize productivity in the face of argument and discussion. Ideas that are better prevail through rigorous verification, always. With public funding, scientists are less bound by profit to come up with a desired result and so this discussion can be more free and less biased. Meanwhile purely privately funded researchers are under immense pressure to produce results that are conducive to their business's bottom line. Again, see tobacco companies, BP, "clean coal" research, and the list goes on.

Your perspective is one heavily reminiscent of a tech-bro entrepreneur, and not of someone who has spent any time in public or private science, or even as a professional scientist at all. You seem wholly unconcerned with the pursuit of truth, which is the fundamental basis of science, but instead of "progress" viewed through an economic light. As someone who has spent many years in both public and private physics, I am curious to know your background. If you did spend time in science beyond a student, I'm curious to know where if you don't mind sharing.

@JamesGrugett Oh and how could I forget the fundamental pillar of science is that information is open and free; something that is antithetical to for-profit institutions. Businesses would keep every single discovery locked behind IP, copyright, patent, etc indefinitely if they could. Scientific literature would cost hundreds of dollars just to access. See Nature, Science, and any other scientific journal before the recent massive push from publicly funded researchers and organizations to pressure them to go open access.

@JamesGrugett And let's not forget that the businesses that are privately funding research are only doing do because of government grants (public) they receive to do so. Without these grants, funding research wouldn't be profitable. The government knows this, and so they provide grants and low- or no- interest loans in order to ensure businesses do exactly what you think they would do in a "free market."

Microsoft and OpenAI?

Boeing and SpaceX?

GE's wind turbines?

On regulation:

Regulation typically destroys value through limiting upside, not in preventing downside. Technology can create trillions of dollars of value out of nothing. Obvious examples in our world are airplanes, electricity, smart phones, etc. But regulation killed flying cars (100% serious lol). It prevented nuclear power from following its cost reduction curve which was reducing exponentially until the 1970s green movement. The ban on human cloning and modification of genes is greatly reducing human capital. Public schools & universities are inefficient, not innovative, and blocking much better private alternatives. The cost compared to what the market would figure out if not restricted is unbelievably large. Same story for building restrictions, immigration, and healthcare (should just be free market). Trillions of dollars of value lost!

Fundamentally, it's hard to imagine the possible upside when you unblock areas for entrepreneurs to build. It's much easier to imagine how adding rules prevents known downsides. But utilitarianism compels us to push for freedom, because the upside is unbounded value.

Why public funding:

Public funding is hard to ever direct efficiently because the incentives are poor when giving away other people's cash.

But, there is an advantage in theory to funding public goods. It's that the goods are public, so they produce value for everyone, whereas if one actor funds it, it they only get a smaller benefit for themselves. Shouldn't that mean public goods are way more effective, like hundreds or thousands of times?

Here's a few reasons public goods are not that much more valuable than private goods:

- The shape of most problems seems to be that there is enough incentive for one party to innovate slightly and then the innovation gets copied rather than staying private. This is how most technology has developed historically. I think it's also how most technology is developed today.

- Big companies with large research labs are willing to spend a lot on research.

- The public goods coordination problem can be solved through mutually beneficial contracts, e.g. kickstarter, where the project is only funded if enough people have pledged toward the goal. See also dominant assurance contracts.

- For critical problems that the market does not solve, there is still philanthropy. I believe without publicly funded science, philanthropists will rush to the scene to fund the most important stuff that companies would not fund.

That's a lot of ways to get around the main value prop of public goods. When you also adjust for how unmeritocratic and inefficient public science is, and how they support many ideas of negative value, then it should be easier to see how private-only science is a good idea.

All that being said, I'm still uncertain on this question, in part because the scope of it is huge and hard to model. But ask a superintelligent AI in 10-20 years. I think it would be closer to agreeing with me than disagreeing.

@JamesGrugett Let me get this straight:

You did not respond to a single one of my points directly. Instead you opted to repeat the same things that I refuted, without argument.

Claim that private investors are outright blocked from funding certain research areas without giving a single example or piece of evidence for this.

Say that when we ask a super AI in "10-20 years" it'll agree with you.

That last point is worth repeating.

You say that you're right because, in your own words, "ask a superintelligent AI in 10-20 years ... it will be closer to agreeing with me than disagreeing."