This question will resolve to the number of original results (out of the two results detailed below) that are also statistically significant in our replication (at significance level of p<0.05, with effects in the same direction as the original results). The second result is split up into two findings, which are given equal weighting to each other. As an example, if hypotheses 1) and 2a) replicated, but 2b) didn’t, this would resolve to 1.5, as hypothesis 1) is given a weighting of 1 and hypotheses 2a) and 2b) are worth 0.5 each.

Please note that we will not be allowing any further time for people to make predictions beyond the listed closing date. (We have previously changed the closing dates for our other prediction markets to allow people more time to make the prediction, but we are not going to do that for this prediction market.)

Original Study Results

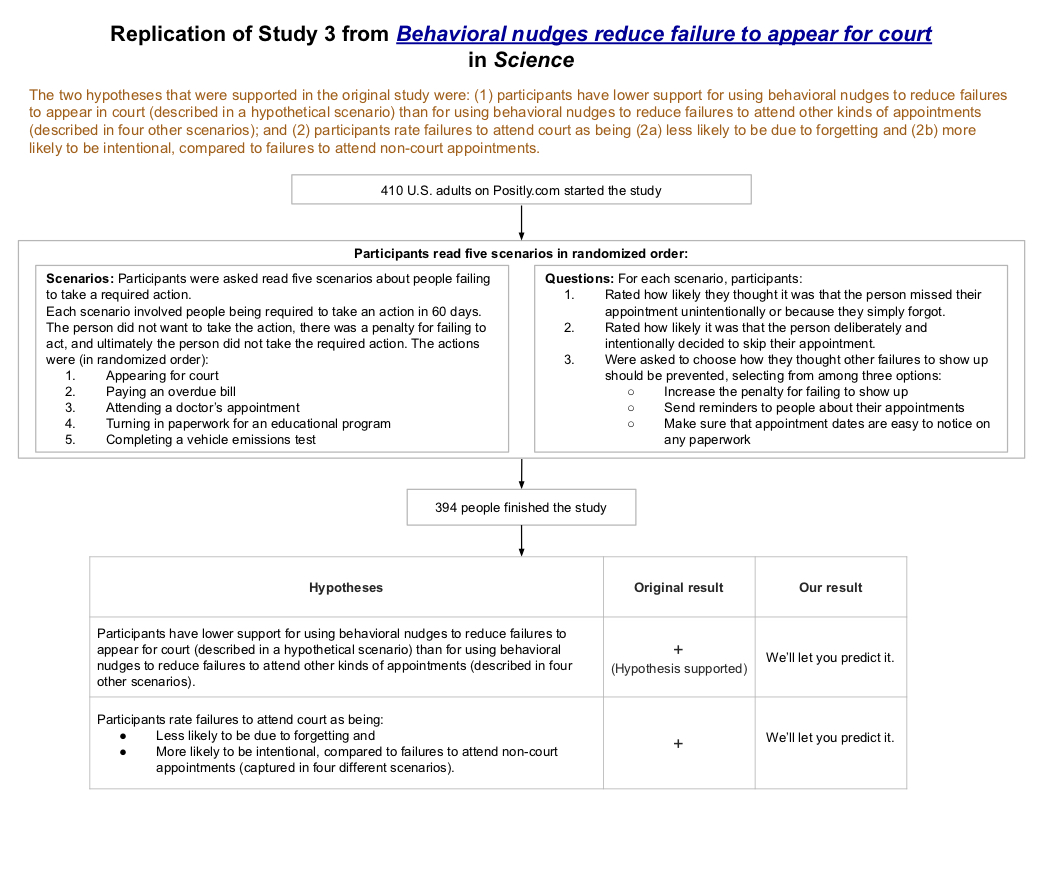

In the original study, participants were less likely to support using behavioral nudges (as opposed to harsher penalties) to reduce failures to appear for court than for using behavioral nudges to reduce failures to attend other kinds of appointments. They also rated failures to attend court as being less likely to be due to forgetting and more likely to be intentional, compared to failures to attend non-court appointments.

Study Summary

Please click here for a higher resolution version of the study diagram

In the original study and in our replication, participants read five scenarios (presented in a randomized order) about people failing to take a required action: failing to appear for court, failing to pay an overdue bill, failing to show up for a doctor’s appointment, failing to turn in paperwork for an educational program, and failing to complete a vehicle emissions test.

For each scenario, participants rated the likelihood that the person missed their appointment because they did not pay enough attention to the scheduled date or because they simply forgot. Participants also rated how likely it was that the person deliberately and intentionally decided to skip their appointment.

Finally, participants were asked what they thought should be done to ensure that other people attend their appointments. They had to choose one of three options (shown in the following order in the original study, but shown in randomized order in our study):

Increase the penalty for failing to show up

Send reminders to people about their appointments

Make sure that appointment dates are easy to notice on any paperwork

In the original study, compared to failures to attend the other kinds of appointments in the survey, participants:

Were less likely to support behavioral nudges to reduce failures to appear in court compared to failures to attend other appointments (M[court]=43%, SD=50; M[other actions]=65%, SD=34; paired t test, t(300)=8.13, p<0.001).

Rated failures to attend court as being:

a. Less likely to be due to forgetting (M[court]=3.86¹, SD=2.06; M[other actions]=4.24, SD=1.45; paired t test, t(300)=3.79, p<0.001), and

b. More likely to be intentional (M[court]=5.17², SD=1.75; M[other actions]=4.82, SD=1.29; paired t test, t(300)=3.92, p<0.001).

The original study included 301 participants recruited from MTurk. Our replication included 394 participants (which meant we had 90% power to detect an effect size as low as 75% of the original effect size) recruited from MTurk via Positly. You can preview our replication study (as participants saw it) here.

¹ This was the mean response on a scale from 1 (very unlikely) to 7 (very likely), after participants were asked: “How likely do you think it is that this person missed their appointment because they did not pay enough attention to the scheduled date or simply forgot?”

² This was the mean response on a scale from 1 (very unlikely) to 7 (very likely), after participants were asked: “How likely do you think it is that this person intentionally and deliberately decided to skip their appointment?”

Background Information

The Transparent Replications Project by Clearer Thinking aims to replicate studies from randomly-selected, newly-published papers in prestigious psychology journals, as well as any psychology papers recently published in Nature or Science involving online participants. One of the most recent psychology papers involving online participants published in Science (Fishbane, Ouss & Shah, 2020) was “Behavioral nudges reduce failure to appear for court.” We selected studies 3 and 4 from that paper for replication.

Context: How often have social science studies tended to replicate in the past?

In one historical project that attempted to replicate 100 experimental and correlation studies from 2008 in three important psychology journals, analysis indicated that they successfully replicated 40%, failed to replicate 30%, and the remaining 30% were inconclusive. (To put it another way, of the replications that were not inconclusive, 57% were successful replications.)

In another project, researchers attempted to replicate all experimental social science science papers (that met basic inclusion criteria) published in Nature or Science (the two most prestigious general science journals) between 2010 and 2015. They found a statistically significant effect in the same direction as the original study for 62% (i.e., 13 out of 21) studies, and the effect sizes of the replications were, on average, about 50% of the original effect sizes. Replicability varied between 57% and 67% depending on the replicability indicator used.

The replication described here was run as part of the Transparent Replications project, which has not run enough replications yet for us to give any base replication rates. Having said that, if you’re interested in reading more about the project, you can read more here. And here is where you can find write-ups for the three previous replications we’ve completed.

🏅 Top traders

| # | Name | Total profit |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ṁ150 |